For our first meeting of 2021, we decided to focus on a science communication topic we haven’t covered before: photography. “A picture is worth a thousand words,” as the saying goes. In this meeting we learned how to make those words count. Because whether you want to be a professional photographer, or just want to use visuals more effectively in the science stories you tell, knowing a bit about how to construct a static image can be a tremendously useful skill to have in your SciComm toolkit.

Our expert for this month’s meeting was Anton Sorokin, a biologist and award-winning wildlife photographer whose work has been featured in a variety of books and magazines.

Screenshot from Anton’s website (you can buy prints there if you like his photos!).

Anton talked to us about how he got into wildlife photography, how he thinks about issues like framing, lighting and mood in the photos he takes, how he uses photography to tell stories, and even what kinds of gear he uses when he’s out in the field.

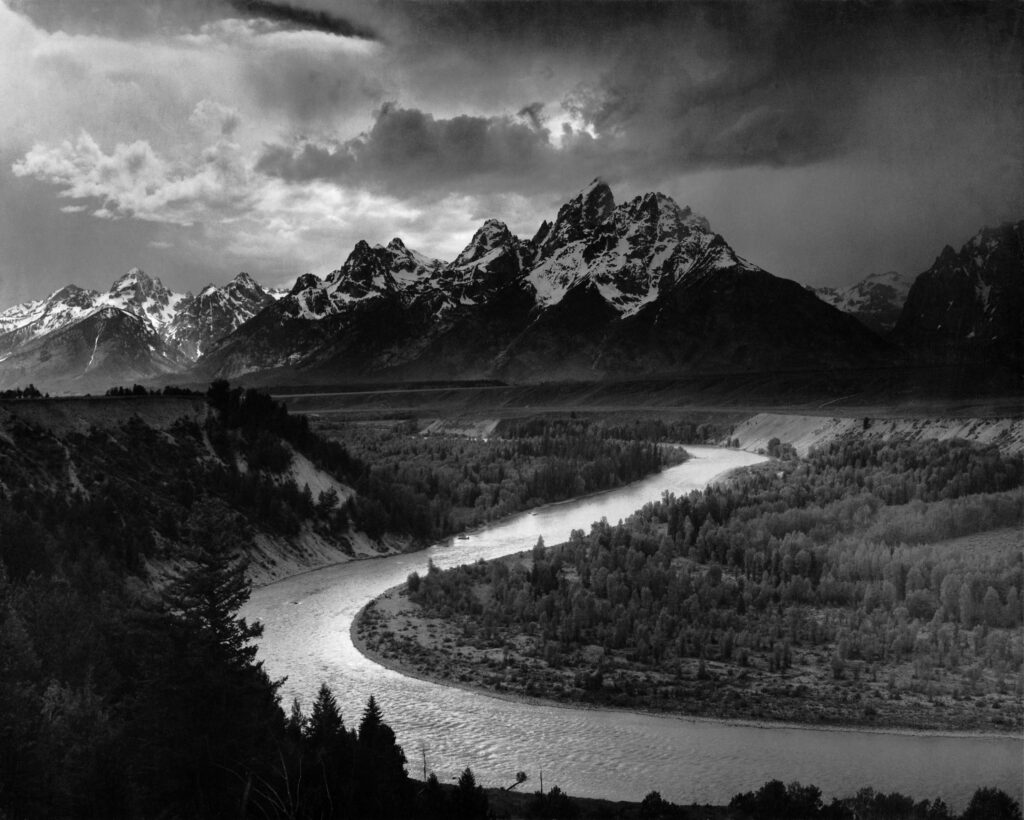

We started the meeting with an icebreaker activity (as is tradition) where we showed famous photos of wildlife or wilderness areas and meeting attendees had the chance to say whether or not they had seen the picture before. Despite the fact that some of the photos were nearly a hundred years old, many attendees were familiar with the pictures we showed, demonstrating the special power photographs have to stick in our minds, as well as the unique storytelling potential of a good picture.

Despite the fact that this photo was taken before Robert De Niro was born, nearly a third of our meeting attendees had seen it before. Ansel Adams: The Tetons and the Snake River (1942).

After the icebreaker, Anton began his presentation. We have provided a transcript of that presentation below, interspersed with his slides. The transcript has been edited lightly for clarity and brevity.

Excellent so I’m glad that we start off with some pictures of mammals, because there’s not going to be a lot in my presentation. As you will see, I pretty much focus on reptiles and amphibians, with a few other things thrown in. So anyway, my name is Anton and I am a freelance wildlife photographer and wildlife biologist currently based in California.

So, to get started, I want to talk a little bit about my path into wildlife photography. It’s been a long process, and I started off as a kid with my parents’ pocket camera basically chasing seagulls on the beach and then getting my parents mad at me when entire rolls of film had to be developed just for blurry pictures of gulls. But I really wanted to photograph all the animals that I saw. Just kind of keep a running life list. Those of you that are birders or herpers can probably relate to that and so at some point it started transitioning more from just taking shots for my own memory to ones that I wanted to share with other people. And they started getting more complex. I managed to go way back in the files and find this shot of a toad I took in 2007. And then, compare it to one that I took just a few years ago, and you can see the change. So before, I was relying totally on whatever light was available to me; the composition is much less interesting it’s taken from above, whereas the shot that I took more recently is much more complex to execute technically and I think more visually interesting as well.

There’s the environment included, there’s external lighting, I actually had to change the focus midway through the exposure to get both the toad and the sky sharp. And I think that one of these images is much more impactful than the other.

The point at which I really started focusing on my photography as opposed to just taking shots for my own memory is is when I was really privileged to work a series of wildlife technician jobs during undergrad. And so I started off working with the Smithsonian in Panama with forest succession, then from that I jumped to Toucans in Costa Rica and then mammalian frugivores In Borneo.

And these jobs really put me on the front lines of wildlife research and I got to see many animals that most people never get to see or most people never get to see up close. And I was sharing my pictures on Facebook and people were talking about how they didn’t even know particular species existed or about the issues facing them, so I started seeing my photography more as a tool to share these experiences with other people outside of my immediate friend group, and also to show some of the issues facing these animals. Because no matter where I went there were threats, whether poaching, habitat loss, inbreeding and so on, and if I could capture that with my camera and raise awareness that would be very important to me. And, as time went on, I ended up working with a few organizations and getting my images published in a pretty wide variety of outlets from museums and zoos to various organizations like Audubon and Smithsonian.

So the most common question that I get as a photographer is what kind of gear do I use– what camera, what lenses I use to capture the images. And this is actually kind of a loaded question for a lot of photographers. A lot of photographers get really huffy and silly about it, saying like ‘you wouldn’t ask world-class chef what kind of skillet he uses, would you?’

But at the same time that’s kind of ridiculous attitude in my mind, because most of us are gearheads and do have a wide variety of equipment to capture the images.

And so I have all kinds of gear and each one of them serves a very specific purpose. So something like this here [pointing to macro lens] I would use to take a picture of something very small because it’s a super macro lens, this [gesturing to a different lens] is a regular macro lens. And in reality, this may seem a little bit overwhelming, but I do want to emphasize that this is not required to get started in photography. 95 percent of the time when I’m out I use three items: my camera body, a macro lens and a single flash. Everything else is kind of for a particular niche of image that I may be trying to capture.

And there are people out there that don’t even bother with that, like there’s people out there doing really amazing work with cell phones. I can’t do that with my phone because my phone is trash. But there’s a lot of people out there, creating really inspiring imagery with a phone. And so it’s really important to figure out what kind of images you’re going to capture and what kinds of tools you’re going to need to capture those so, for example, you probably don’t want to photograph bears with your iPhone. But for something like research it might be perfectly suited that.

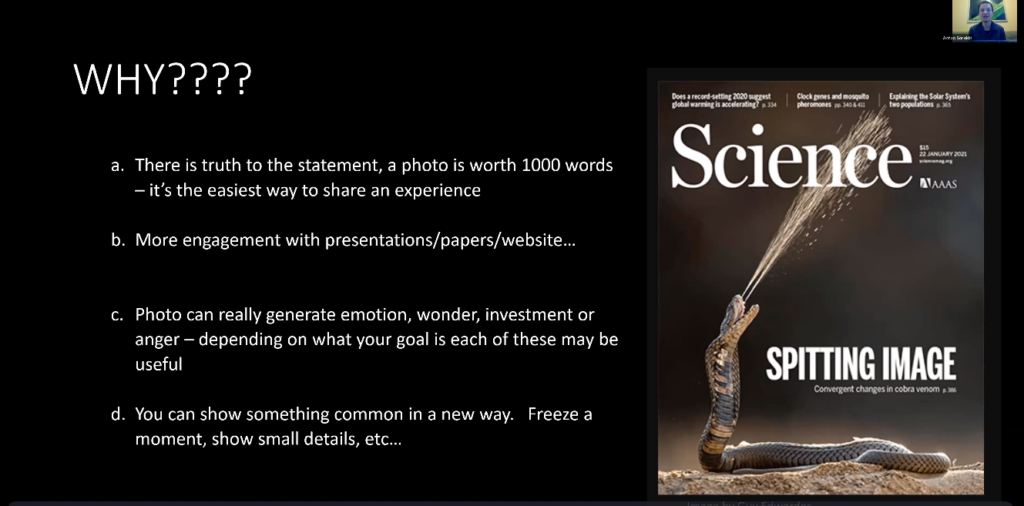

So why take images, in the first place? Why bother? Why think about it? So a really important part of science communication is realizing that humans are visual creatures. It’s a cliché but there’s truth to the statement that a photo is worth 1000 words. Because in just a second you don’t need to convince somebody to sit down and watch a video; in a second, you can show somebody the scene, what you want them to see.

This can be used to generate emotion, like some of those images that Bradley started with were very emotional like the dead gorilla being carried. Or the mountain lion by the Hollywood sign. Those probably connect with you on some emotional level; just hearing a description probably wouldn’t do.

And so, then you can show something common in a new way. So imagine some bird taking a bath something you’ve seen probably dozens of times. But if you freeze the moment in a way that the human eye doesn’t really perceive, like with flying water droplets or every feather ruffled it can generate the sense of awe for even the familiar or small details that we might not normally see with our eyes, like pollen grains stuck on the hairs of a bee. And that can help communicate your message.

Then, as researchers, journalists, and people interested in science, we often do presentations. And these presentations can become much more engaging if they’re paired with strong visual imagery that helps tell the story. Same thing with academic papers– your website can look really professional and attractive if you have high quality images.

And this is an example here with a cobra; just last week there was a pretty cool paper published on the co-evolution of cobra venoms. So normally, without the image, that might be interesting to a pretty small niche group of people. But then you pair it with this image, where you have this snake, with its head raised, hood flared, mouth open and twin jets of venom springing from its mouth, that’s really eye-catching and impactful and I have seen this getting passed around quite a lot on social media. I think that part of the success there is definitely the really attention-grabbing images that are paired with it.

So with any photography, wildlife and otherwise, you have to ask yourself why are you taking the images, what are you trying to communicate to the viewer. And then, when you are focusing on wildlife, there is another level to it where you can ask yourself what makes a species interesting, what’s unique about it, and try to incorporate that into your photos. So here on the left, I have a picture of a lizard from Peru. And this species is interesting in that it lives in kind of unusual aquatic environments for a lizard– small jungle streams. And so in order to communicate that interesting aspect about its biology, I wanted to show that off, and I think it makes for a much stronger image with that running water right next to a little bit of fill flash to bring out the color of the lizard.

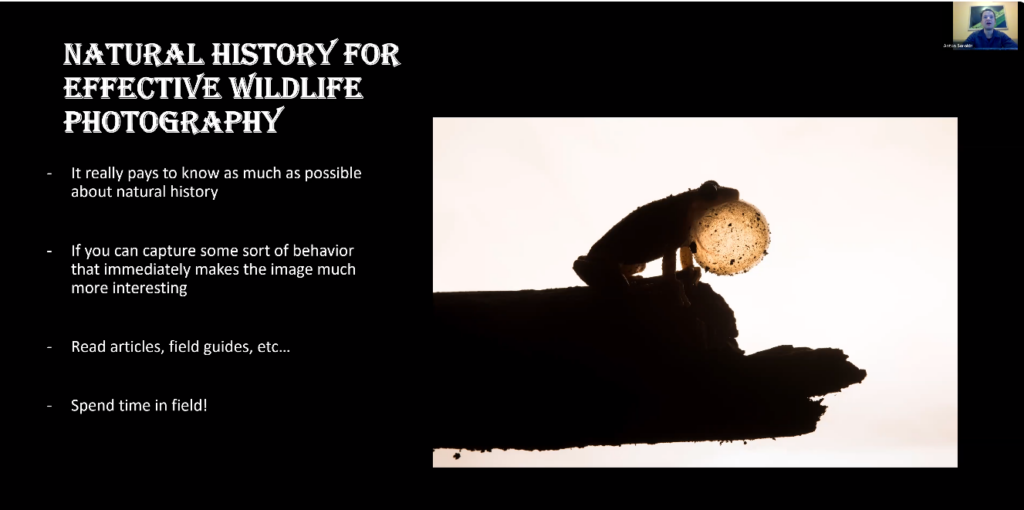

And that brings me to my next point about natural history in wildlife photography/ So my main piece of advice to people that are starting out in wildlife photography or people that want to take their science photography to the next level is to consider the natural history and to acquaint yourself with it as much as you can because unless your species is really rare or stunningly beautiful, a static shot of it is only going to go so far.

The shots that are most interesting and have the widest appeal are pictures of animals doing something. And in order to be able to get those images it really pays off to think about the natural history, so what time of day is it active, what season, what behaviors it might display and how you might go about photographing that. Then you can think back to your gear and decide what you need to capture that. So I’m always voraciously reading through new papers that are coming out about the animals that I’m interested in– things that might describe behaviors that have never been photographed before or aspects about their activity.

And then there’s also spending time out there, observing them so there’s no substitute for that and it doesn’t have to be sitting in a blind in the Serengeti for months on end. Like, in this case, this was from when I was living in North Carolina I would go out a couple evenings a week and just stroll through the wetland behind where I was living and I figured out when the spring peepers were calling what their behavior was, and I was able to set up for the shot that shows this male frog calling to attract a female and frame it in a dramatic way.

Another time I was co-instructing a field course in Ecuador and I took a night hike and found this species of fairly drab brown toad perched on the forest floor and I noticed that its skin was beginning to slough off a little bit. And by knowing a little bit about the natural history I knew that it’s really common for amphibians to consume their skin to recycle the nutrients when they slough their skin off. And this is something that’s really common but doesn’t get photographed very frequently, so I was hoping that I could do it. And I kind of settled down next to the toad and waited and once it became a bit more comfortable with my presence it continued pulling its skin off itself like a sweater and eating it. Which made for a much more interesting image then just a static portrait of the toad just sitting there, if I had just not really realized what the sloughing of the skin meant.

This next photo was taken just a few days after the other image; this one is a cane toad and it is a toad that has been photographed very widely across the world, where it’s invasive in many areas. But, as I was walking up, I noticed something about the toad’s posture that indicated that it was hunting, that it was focused on something.

And by looking out and kind of scanning the environment I was able to see the stick insect that I had entirely missed. And I settled in and kind of waited for something to happen, and they were in the standoff the toad is waiting for the stick insect to move which would signal to that there’s prey and the stick insect was staying still to not get eaten, and in this standoff I was actually the first to leave because I didn’t have the patience to stick around! I lay on the forest floor for like half an hour and then I decided that it was time to move on but this, I think, made for a much more interesting shot than just the toad on its own, and the reason I was able to get that was because I recognized something about the toad’s behavior.

Moving on, these two images are both ones that were published as part of research that I was involved in.

And these kind of also include this aspect of luck, because, even if you know all the natural history there’s only so much that you can plan for. So in this case, on the left, this is the first record of inter-specific combat in glass frogs. So it’s two males from two different species kind of wrestling over territory, and this would be very hard to plan for because it’s the only time this has ever been recorded. But knowing about the natural history of the glass frog when I was out there and looking for it put me in the right spot at the right time to see this, while I was wading through a river in the middle of the night, scanning vegetation that was overhanging the running water– not somewhere that I would end up by chance.

And again, I talked earlier about images being really useful in generating interest in scientific papers– this was a part of a national history note that we published. And it was paired with these interesting images, which I see get shared around every now and again on social media.

Then the cockroach on the right, that is a species that was described in 1912. And there’s just not any information about it really; people have taken a few pictures of it, but nobody really knew anything about it.

But once the reserve manager told us about uncovering a nest of these living in a fallen hardwood tree, we were able to do the first behavioral observations of it and kind of just sit there watching the nest and observing it and learning about its natural history, seeing when it would come out from that nest, what hours it is active, etc. And we were able to get the first images of any behavior. So here it’s feeding on algae. And we know a little bit about its diet now. We were able to make a hypothesis about fairly unique social structure in the species and again pairing it with high quality images really gave it a lot of steam.

This next photo is a more recent one from closer to home here in California, the California red-sided garter snake.

I wanted to get these images that were attention-grabbing and showed the most colorful version of this subspecies because they’re pretty variable across their populations. There’s ones that are actually fairly drab and there’s ones that are brightly colored with the red and blue like you see here. And there’s only a couple populations, where they actually feed on these California newts which are really toxic, they have tetradotoxin. And I would have never been able to photograph this without doing my research ahead of time and without learning about these snakes. I was able to figure out where they go to hunt, and then, when I got there, to sit back and observe them hunting a little bit and put in not very much time at all to photograph this. It was the national history knowledge that really paid off.

And then, so I mentioned earlier about using your images to tell a story. Oftentimes as biologists, we see things that we want to communicate to the public. And we want to raise awareness, or to show something in a way that inspires movement because, for example, conservation is all about inspiring people to care and want to do something so sometimes when you’re doing this, you have to just remind yourself to include the human element of a picture or include things that are not as photogenic. So my example here is this barred owl from North Carolina. When I first saw it, I took a couple images of it sitting in this tree and the image is fine. I think the plumage is pretty, it’s a cool bird, the exposure isn’t bad. But this image, at the end of the day, I would argue, is pretty forgettable.

It’s not going to stay with somebody. But by looking around at the scene a little bit I was able to step back, using the same lens, using almost the same position, I was able to photograph it in this really contaminated environment and show a picture that I think is much more meaningful, that stays with the viewer. It’s kind of shocking seeing wildlife persisting in environments that are choked with human pollution and this image has been pretty well-received and whenever people see it, they tend to be angry and ask about like, how can we fix this, can we organize a cleanup.

So this is something that took me years to remember to do in wildlife photography: sometimes it’s not just about showing a pretty animal it’s about showing the situation that it’s dealing with in what can be an unappealing way.

Continuing with the theme of telling a story, it’s really good to include people when you can. So here is a biologist doing moth lighting, basically surveying for insects and it’s only a snapshot so it doesn’t tell a complete story. You don’t know what the biologist is exploring about these insects or really what’s going on. But yet it can be used to illustrate a wider message. So I’ve had images like this license pretty frequently for illustrating stories about the insects decline that is ongoing. It’s always good to include people if you can just because those images tend to speak loudest to people that may not be interested in moths otherwise, but they look and they see somebody doing something, like a researcher investigating an issue, then you can try to illustrate ongoing problems in ways that are a little bit different.

Another example of remembering to include the whole scene is this image. Here I was really tempted just focus on the birds, but looking around at the scene, not getting hyper-focused on the wildlife itself, I was able to take a step back and zoom out and include the windmills in the background. And this image has actually been very popular with a couple organizations. So Audubon licensed this one not too long ago for a commentary on renewable energy and birds. The take home message there is just to remember to look around and include the wider picture.

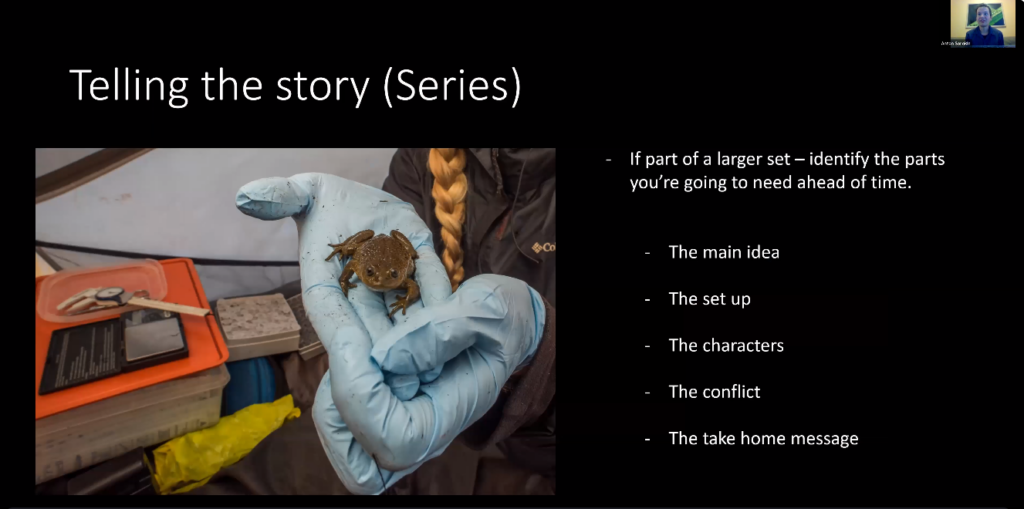

And then, sometimes you have more than a single image to work with, so you can get much more in depth with your storytelling. This is really good if you’re doing a presentation on your research or if you’re a journalist working on a story and you want to supply the photos as well. Or if you’re submitting images for a popular science piece on your research.

Just like with creative writing, I think you need to identify the parts that you are going to need ahead of time. And it pays to sit down and plan the story out because there’s no worse feeling than coming back from the field or coming back from a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and realize that you missed some shots. That really is critical for the deeper story and I learned that the hard way. There’s been many times where I got back and kind of thought to myself ‘oh my God did I not get this shot? That is what the entire story is about! I got all these like filler shots but not the main one!’

So sit down ahead of time and plan it out. Every story is going to be different and it’s going to need different components, but the ones that are pretty consistent across whatever spectrum of story you’re working with are the main idea, the setup the characters, the conflict, and the take home message that you want people to leave with.

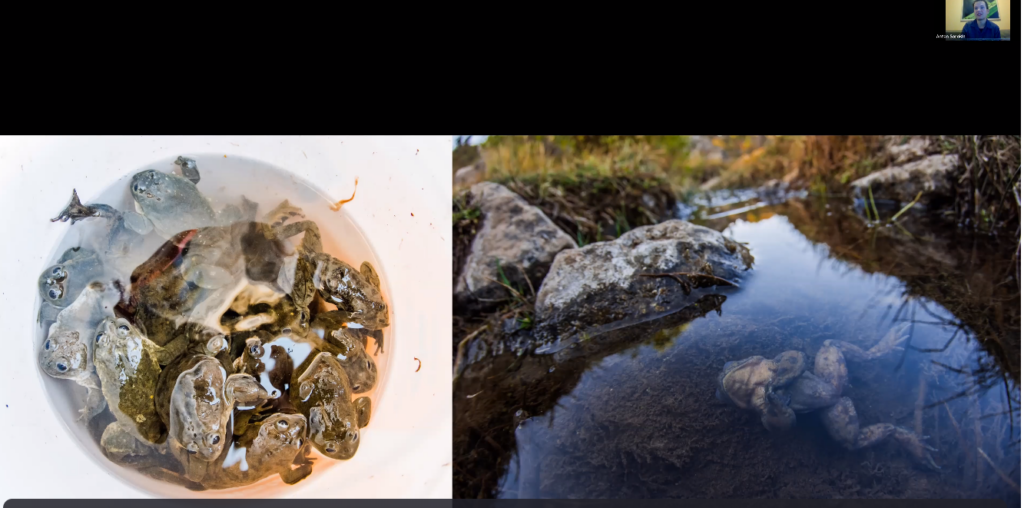

And I’m just going to kind of run through a photo story that I am working on that hasn’t found a home yet and I still need to finish it up. But it is about the ongoing research about the highest elevation frogs in the world that live in southern Peru in the Andes at an elevation of about 5,400 meters above sea level; something like 17,000 feet, which is higher than any point in the lower 48 states.

So first is the setting. Even though this doesn’t include any wildlife, it’s really critical for the viewer to see it in order to appreciate the intricacies of the story that I’m trying to tell; to be able to imagine where it’s happening. So here we have the kind of like high Andean habitat, as well as a glacier that is one of the glaciers that is receding; it’s melting due to climate change. And as it recedes, these frogs are able to move upslope and colonize this newly opened up habitat. And they’ve been moving steadily upwards, but unfortunately, as the glaciers vanish the water that the frogs rely on also vanishes so it’s probably for me a temporary facet of their conservation.

Anyway, then you want to introduce the characters. So the species that the entire story is about. So here I have the marbled four-eyed frog on the right and on the left is the marbled water frog. And I’ve included a picture of them in the wider context, so if you’re short on space that can be good to kind of combine the setting with the characters. And you can see the type of environment that they live in.

But at the same time that doesn’t really oftentimes work as well as a much more intimate connection with the subject. So here I contact with this frog, this is the marbled water frog again, which I have taken from a lower level so that the viewer’s on the same point because we’re better able to feel or identify with the species more when we have eye contact as opposed to looking down on it, which we would normally be doing since we’re so much larger than these frogs.

And then, this next portion is going to sound super obvious, but I have made this mistake many times: don’t forget about the human element. Whether it’s you as the researcher or the researchers that you’re reporting on, they are a critical component of this story. The story is incomplete if you don’t include people. So I worked in Borneo and Ecuador on various projects where I wanted to take photos and I realized after the fact, looking back that like I just took pictures of the animals.

And this happens sometimes, sometimes my pictures don’t have any people in them. And when they do I’m missing this huge component.

It’s also good to take pictures of everyday life. So here on the left a blizzard had come through the night before and the frog team is sitting there having breakfast looking miserable. And then on the right they’ve captured some tadpoles. They’re holding them up and the weather is quite rough but it shows some of the challenges that the team had to deal with and really helps you connect with the people. A lot of people care about wildlife but almost everybody cares about other people I’d like to think.

Then there is the conflict. So the conflict is of course important to portray and, in this case, there’s a few different forms of conflict in the story some which are easy to picture and other ones require a little bit more thought.

So these first two are really easy, so these frogs are poached for these frog shakes that are thought to be of medicinal value. There’s nothing to support that but unfortunately they’re being taken and thrown into these blended up frog shakes to treat all kinds of ailments from memory loss to impotence and whatever. So this picture was taken at a market in Cusco; it’s not my best picture because the person selling the frogs changed her mind halfway through about allowing me to photograph them. But you can see that they’re crammed in there, the waters kind of rose tinted from where the frogs have like rubbed their skin off rubbing against each other. It’s a pretty sad picture, all these frogs are going to die in a really non-humane way as well. And so they’re being taken from the wild at an unsustainable rate because being a very high elevation species, they grow very slowly and almost any level of harvest is unsustainable, with them.

And the picture on the right is a dead frog in a otherwise pristine water body. And it’s meant to illustrate the effect of the Chytrid fungus on these frogs. So the Chytrid fungus is this fungal pathogen that has swept through amphibian populations almost worldwide causing unprecedented levels of extinction and population declines and it’s also affecting the frogs high in the Andes. This particular species the story is about have been recorded dying off due to the fungus so it’s really obvious how to portray that– just a dead frog in water that likely died of Chytrid.

But then sometimes there’s more abstract issues going on, like, how do you take a picture of climate change. Unless you have access to some historical pictures and can show a glacier shrinking this can be really difficult in the moment. But if you think about it a little bit and look around oftentimes you can show a snapshot. So here we have one of the local members of the frog team looking at this shrinking glacial lake that gets most of its water from melting glaciers, which at this point, have melted beyond the point of being able to supply the water, so the lake is shrinking. This mud flat appeared in just a year since we’d last been at the site.

And then another shot that I wanted to include about illustrating the problem is sometimes you may want to take an abstract way of communicating an issue as well because it’s really easy to overload an audience with these really brutal images of dead or dying animals. Sometimes it’s better to have something a little bit more metaphorical. So here, I tried to include this ghostly toad kind of like blowing away into the sky. It’s a little bit more confusing of a shot, but I think works better for a lot of the issues, just because nobody wants to look at pictures of dead frogs. But this might resonate with audiences a little bit more.

And then, of course, you want to end with the take home message, often kind of upbeat if you can just because nobody likes ending things on a negative note. And I wish I could show that everything is going to be okay for these frogs but we don’t know that. But I can show that there are groups of dedicated, passionate people working really hard to understand the issues to learn more about these frogs and that care about the animals. People that are invested in that ongoing work. So one of the things that I mentioned is that this story is ongoing and I do want to use a photograph of some of the lab work. But that has been difficult because of pandemic restrictions and getting permissions to go into the lab but I’m hoping that actually sometime in the coming weeks I’ll be able to photograph that work and then hopefully the story will find a good home somewhere. We will see.

To wrap things up, I frequently get the question about getting paid and there’s a lot of different ways that you can get paid as a photographer and make a living. It’s difficult, it is not my sole means of income, but there are various ways, some of them are really self explanatory but other ones are a little bit more complicated like partnering with organizations. I partner with a few NGOs down in Peru and I sometimes reach out to other organizations and there’s not always a monetary benefit that these organizations are able to offer, but, for example, I have an email that I plan to send out this afternoon to an organization about documenting their work and getting the ability to access an island that would actually be off limits to me by providing them with high quality images and also being able to tell the story for myself and potentially pitch it to a magazine. And it’s mutually beneficial; they don’t directly pay me, but hopefully down the road it will result in some monetary benefit.

Then there’s non-traditional methods like consulting. You may remember the images of the garter snake that I shared. So when I shared those on social media shortly thereafter, I was contacted by a nature documentary film crew about helping them film the same thing for a documentary they’re doing on California wildlife. So once the weather warms up a little bit I’ll be going out there with them trying to help them get the footage and now this isn’t directly photography but it’s a direct result of my photography.

Finally, no presentation on photography is complete without at least some mention of ethics, because it’s really important. You don’t want to mislead your audience and you don’t want to be an unethical photographer. So you can do a whole presentation on this but it can really be distilled down to two major points. First, no shot is worth your safety or subject’s safety. So every year there are stories about people getting killed by the wildlife they’re attempting to photograph, whether it’s bears in Yellowstone or elephants or crocodiles, what have you.

But there are a lot fewer stories about the effect that photographers can have on their subject’s safety. So nobody does a story about an owl they flushed that got eaten by a red-tailed hawk or something like that, or a bird nest they caused to get depredated. And really this again just boils down to being able to ascertain whether you’re taking the photos in an ethical, safe way for your subjects.

And it also comes down to knowing the natural history. Like you can get a lot closer to a frog with a camera than you can to a bear; you know that one’s a massive carnivore and the other one the small squishy little amphibian.

And then also if your goal is photojournalism be honest about your photography. It’s fine to have like artistic images that don’t really represent things as they were but it shouldn’t be passed off as photojournalism. So there’s been a few big scandals over the years, but the one here in the top is a big one from a few years ago. This Brazilian photographer won a lot of accolades with this picture of an anteater eating termites from this termite mound that was also covered in glow worms. But then a couple years later it turned out that the anteater in the picture is taxidermy. So he got into a lot of hot water for that and lost his reputation. That’s just one of many examples like this.

And then also you’ve probably seen this: viral images of frogs riding turtles and whatnot that are portrayed as if the photographer found this frog and found it making friends with a tortoise. Obviously, people just stage those with pets and don’t include the relevant information and that’s unethical as well just because it really muddies the water for honest photojournalism and honest reporting on animal behavior.

And then I’d like to end by giving a shout out to some people that I really suggest following if you’re interested in photography or wildlife. So there’s Anond Varma, who is a National Geographic photographer who does a lot of studio photography. His images are really great at communicating science and just have this like really cinematic aspect to them.

And then there’s Morgan Heim. Her images really focus on empathy with nature. Chien Lee focuses on tropical biodiversity and has really incredible images of everything from flora to clouded leopards and everything in between. There’s Jen Guyton who does amazing camera trapping work and other work in Africa. David Herasimtschuk who is one of the best underwater photographers out there, and especially focuses on fresh water, which is under represented. Piotr Naskrecki does incredible macro work. And Esther Horvath who is less about wildlife, but more about documenting the research being done in polar regions by scientists.

And like I said, these people are all at the top of their field and you won’t regret checking out their work it’s just amazing eye candy and amazing inspiration.

And of course there’s me if you want to follow, along with me on any of the social medias: Instagram or Twitter if you have questions about anything you can reach out to me check out my website.

And I am happy to answer any questions that you guys may have now, thank you for listening to my talk.